By: Adena Adams

[Author’s Note: The following essay was written for my Craft of Writing course Fall Semester 2017. In this essay I analyzed a chapter in Marjane Satrapi’s graphic memoir Persepolis and discussed the ways in which Marjane’s emotions are tied to her identity and family.]

Marjane’s Emotional Journey

Marjane’s cultural identity is rooted in her family. Up until she moves to Vienna, family has been the one constant in her life, no matter the circumstance. We know that throughout her young life, Marjane struggles to find her place in the world, but in the chapter “the Vegetable” Marjane’s separation from her family at the start of her adolescent years forces her to find a “surrogate” family within Western culture. At this stage in her life, Marjane is just entering puberty, meaning everything about herself is changing, from her physical appearance to her emotional state. Feeling angry and confused, she ends up distancing herself from her native culture, choosing instead to conform to “rebellious” Austrian “punk” culture that encourages a negative outlook on life. Despite this, Marjane’s emotions are tied to her family as well as her sense of self and it is these emotions that ultimately reconnect her with her heritage and solidify her sense of cultural identity.

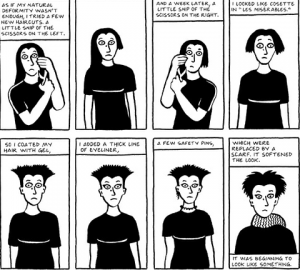

When it comes to her own identity, Marjane’s doubts surface as her physical appearance begins to change at an alarming rate. To show this phenomenon, , Satrapi draws her sixteen year old self as a Hulk-like monster in the first panel of the chapter (189). Textually, the panel describes the “metamorphosis” that we the audience understand to be puberty, but visually, it depicts Marjane’s state of mind. In the panel, Marjane is drawn with a confused and almost angry look on her face, as if the suddenness of her transformation has caught her completely off guard. She is surrounded by sharp, tumultuous lines that seem to radiate off her body. Satrapi uses these angular lines to further convey this sense of confusion and anxiety as “a distorted or expressionistic background will usually affect our ‘reading’ of characters’ inner states” (McCloud 132). Here Satrapi’s use of interdependent panels, panels where words and pictures come together to project an idea that neither could do alone, also serves to reflect her sixteen year old self’s state of mind. The text suggests that Marjane’s “mental transformation” has already passed; however, we know from looking at the picture that it is far from over. In fact it continues through more changes to her outward appearance, though this time the changes are made by Marjane’s own hand. In this sequence, little by little, Marjane cuts and styles her hair, experiments with makeup and garnishes herself with accessories. In the last panel of Fig. 2. Marjane has spiky hair, thick eyeliner and a scarf.

Again, Satrapi uses lines to convey a sense of anger and confusion. The pattern used on Marjane’s scarf is identical to the lines radiating off Marjane’s body in Fig. 1. It is sharp and angular, giving off the same anxious and angry vibes. However, these sharp lines are contained in soft, rounded lines. These conflicting lines reflect Marjane’s repressed inner turmoil, which stems from her anger and frustration at being thrown into a culturally different environment, as well as her outward complacency “to go with the flow” and assimilate to Western culture. Satrapi hints, however, that this repressed state is not to last forever. Marjane’s hair is drawn pointed and unwelcoming, so that her seemingly neutral face takes on a volcanic or explosion-like shape. This use of line and shape foreshadows the “eruption” of emotions we know Marjane experiences towards the end of the chapter. Before she reaches this point, Marjane’s frustration at being without her family turns into guilt from “betraying” them. Her first major exposure to the differences between Western and Iranian culture having pertained to “the sexual revolution,” Marjane’s subsequent experience pertains to drug abuse. Her new European friends “rebel” by smoking marijuana at school, and she joins them “out of solidarity” ( 192). Though she only pretends to inhale the smoke, she is still conscientious toward her parents and ends up with a feeling of guilt. Because Marjane has already changed her appearance to a Western “punk” look and now participates in activities frowned upon by her native culture, she cannot help but feel as if she is deceiving her parents and ultimately herself. She has only been in Vienna for a few months, but by going so far to assimilate she feels as though she “was distancing [herself] from [her] culture, betraying [her] parents and [her] origins” (193).

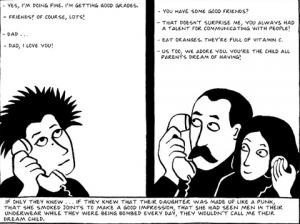

Fig. 3. is an interdependent panel where Marjane is having a telephone call with her parents. The inner text and picture show Marjane having a pleasant conversation with her parents, who are showering her with kind words and pride. With the outer text, Marjane tells the audience that these talks evoke a sense of shame in herself. Even the design of the panel instills a sense of “traitor’s guilt,” Satrapi draws herself and her parents holding phones and facing each other, separated by a thick “wall,” It is almost as if they are on opposite sides of a prison phone booth, furthering the idea that Marjane sees herself as a sort of criminal, in prison for treason against her family and her culture. This idea of deception and guilt continues as Marjane then proactively tries to avoid her past, thinking she can ease her guilty conscious by simply forgetting everything from her past. However, to forget one’s heritage is to forget one’s self and forgetting herself only serves to hurt and confuse Marjane more.

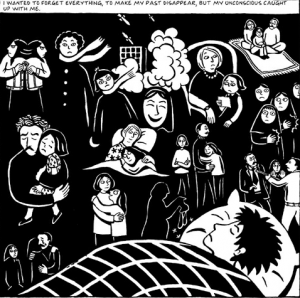

In Fig. 4. all the memories and emotions that Marjane tries to suppress are bubbling back up through her unconscious at night. In most memories her family is there to comfort her when she is sad, teach her when she is confused and embrace her when she is happy. The others are events that left strong feelings with her, for example, anger when she attends her first demonstration or sadness when she saw her uncle Anoosh for the last time. Because her family cannot be in Vienna with her, these memories and emotions are all the more important as they are the closest thing Marjane has to guidance.

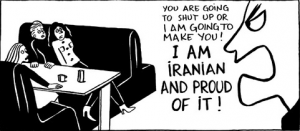

In this entire chapter, Marjane suppresses her feelings in order to find a place in Western society. Finally, in a burst of rage, Marjane frees her suppressed emotions. After attending a party where she denies her Iranian nationality, Marjane overhears a conversation between girls at a cafe near her school. They begin to insult her and as she hears them call her “ugly” and a “cow” she merely sinks lower in her seat, looking almost defeated (196). However, Marjane doesn’t get truly angry until they insult her relationship with her family stating that “her parents clearly don’t care about her, or they wouldn’t have sent her alone” (196).

In Fig. 5. Marjane finally erupts, unabashed and unashamed of her heritage. In this panel Marjane is drawn from the side creating a profile. Gone is her westernized look, with the hair cut to look “punk” and the scarf, so that the only thing you see is her face and its enraged expression. Marjane has always been a strongly opinionated and unafraid to speak her mind; after all, it is what got her sent to Austria in the first place. Her anger here is liberating, as she lets her repressed self-go. With this cathartic release, anxiety and insecurity are replaced with relief and a sense of pride.

After struggling to adjust to her environment as well as her feelings, by the end of “the Vegetable” Marjane has finally adhered to her grandmother’s advice. She learns that if she cannot accept her past and her own culture that make up parts of who she is, how could she successfully ingratiate herself into a new culture? Many people in Europe at the time may have viewed Iran as a place full only of extremists, capable of inhumane evil, but this memoir we know that is not true, Marjane especially. The people of Iran have been through political and cultural turmoil for generations, but they remain a proud people with a rich culture who deserve respect and as Satrapi says “should not be judged by the wrongdoings of a few extremists” (Intro). Marjane carries with her this same sense of pride and anger and love and justice that comes from her and her country’s past. Her heritage is rich and complex like Iran itself and if she it is this part of her that she learns to take pride in. By the end of this chapter, Marjane may still be at odds with Western culture, but at least she knows who she is and where she comes from and she is comfortable with that.

Works Cited

McCloud, Scott, and Mark Martin. Understanding Comics: the Invisible Art. HarperCollins, 2014.

Satrapi, Marjane. “‘The Vegetable.’” The Complete Persepolis, Pantheon, 2004, pp. 189–197.